|

Sheffield ‘University of the Third Age’ Classical Greek Group (Sheffield U3A Classical Greek Group)

‘’ What is the point of learning Classical Greek? You can’t use it.’’ This encouraging reaction to what I said I was doing now that I had retired took me aback. ‘’So that I can read the writers and thinkers of the Classical Era in their own language,’’ did not dispel my questioner’s scepticism about the value of the pursuit. Fortunately, there are other Senior Citizens in Sheffield and South Yorkshire who are equally passionate about the language and literature of the Classical Greeks: eleven of us meet fortnightly in the Sheffield U3A Classical Greek group. Roughly half of the group is learning the language from scratch following a GCSE course book. The other half is already very competent in reading and writing in the language. At the moment we are enjoying Herodotus, Histories, Book 1, especially the writer’s occasionally incredulous comments regarding the customs of peoples beyond his own experience as a Greek. Last year we completed reading the whole of Homer’s Iliad, Books 6 & 22. Two members have been sufficiently inspired by Homer to compose their own verse translations of the Odyssey and Iliad Book 22. We have also dipped into Thucydides, Euripides, Sophocles, Xenophon, Plutarch, Aristophanes, Apollodorus, Demosthenes, Lysias, the New Testament. The choice of authors and works is decided by members; we are always willing to try lesser known writers and works, as well as the more popular. Lest anyone should think that advanced age rules out the use of modern technology, you need to see us in action exploring classical resources on-line – with Ipad, smartphone, notebook or laptop! What a difference from the ‘good old days’ fifty or 60 years ago when dust was likely to settle upon you, as you spent hours consulting dictionaries and grammar books, slowly extracting a translation for your ‘set book’. By contrast, what a pleasure the process is today! A couple of questions for lovers of Homer: in the Iliad

Did they ever meet?

Deidre Eastburn Coordinator, Sheffield U3A Classical Greek 19 September 2016 (Answers:

0 Comments

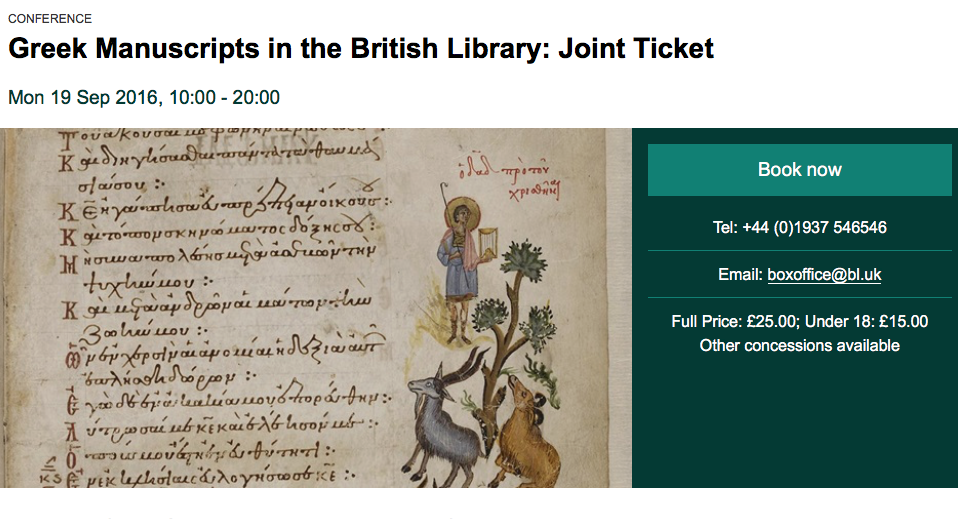

Michael Wood at the British Library last night, making connections through digitised Greek manuscripts . . .  What's the Connection between Plutarch, the modern Greek poet Cavafy and this modern master-piece? Also here's the manuscript of Plutarch that's been part of the British Library recent digitisation project.

The Berlin Painter decorated the neck only of a glossy black amphora in about 490 B.C. It shows Achilles overcoming Hector. As usual, the victor is shown on the left: the conquered hero falters and drops back. The Berlin Painter decorated the neck only of a glossy black amphora in about 490 B.C. It shows Achilles overcoming Hector. As usual, the victor is shown on the left: the conquered hero falters and drops back. The study of Ancient Greek continues in Sheffield! Every week groups of eager students gather to practise their grammar and Syntax (!) and read Literature that has survived for thousands of years and is still vividly alive today. Names of authors such as Sophocles, Euripides and Herodotus are part of the common parlance when these groups meet. They form part of the Sheffield branch of the U3A (University of the Third Age). There follows below a translation by a member of one these study groups, Peter Pond. Peter and his colleagues were reading part of the Iliad of the poet Homer (Book 22), during which the Trojan Prince Hector meets the Greek hero Achilles in single combat outside the walls of Troy. If you want to find out what happens read on! Homer's influence was powerful in all aspects of Ancient Greek Literature and still resonates with us today. If you want to try some of the original Greek, click here or follow the link to the U3A above. We hope to publicise regular news of the Classical activities of the U3A ( and any other pockets of Classical resistance!) 1. And while, like fawns, the Trojans downward through the city fled, 2. And panted out their sweated breath, and drank and slaked their thirst, 3. Reclining on the handsome battlements, meanwhile, the Greeks 4. Were getting ever closer to the wall, on shoulders shields inclined. 5. But Fate destructive shackled Hector, making him stand fast 6. Down there before the mighty Scaean Gates of Ilion. 7. And now Apollo, known as Phoebus, to Achilles spoke: 8. "Achilles, why pursue me still upon your nimble feet, 9. When you’re susceptible to death, not I? Do you not see 10. That I'm a god, and yet you chase me on with so much fire. 11. To you, the fight with Trojans, now repulsed, seems quite forgot, 12. For they have citywards escaped, whilst you’re diverted here. 13. But you will kill me not, since I no subject am to Fate." 14. But then replied Achilles, swift of foot, so deeply vexed: 15. "You've thwarted me, you striker from afar, most dreaded god. 16. Just now you turned me from the wall: else many more would then 17. Have ground their teeth with earth before they made their way to Troy. 18. And mighty glory have you robbed of me, and rescued folk - 19. No danger to yourself, since retribution none you fear. 20. But I would make you pay, if only I had got the power." Medieval and Ancient Research Seminars Humanities Research Institute, 34 Gell Street, S3 7QY 5pm drinks, 5.30pm paper begins 5 October 2016 Hugh Pyper (SIIBS) Cassiodorus and the Crisis in Humanities.  Cassiodorus – his full name was Flavius Magnus Aurelius Cassiodorus Senator – is one of the less well-known, but nonetheless fascinating, characters of the later Roman period. He was born into a wealthy family in Calabria, on the toe of Italy, in about 485 AD. He trained as a lawyer, and went to work first for Theoderic, King of the Ostrogoths, then for his successor Athalaric. He kept copious notes and meticulous records, and his work was so much admired that when he was in Ravenna – these days famous for its beautiful mosaics of Justinian and Theodora, created some time later in about 547 AD – he was entrusted with writing important public documents. He rose to become Praetorian Prefect of Italy, which meant that he was in effect the Prime Minister of the Ostrogoths. He was very interested in literature, and in collaboration with Pope Agapetus I he founded a library of Greek and Roman texts in Rome, intended for Christian educational purposes. Political turmoil forced him to move from Italy to Byzantium, where he lived for the next twenty years or so, trying to bring about unity between East and West, Roman Greek and Gothic cultures, and the Orthodox and Arian religious divide. On retirement, he founded the monastery of Vivarium on his family estates in Calabria and spent the rest of his life there engaged in religious writings. Professor Pyper writes in advance of his lecture: At a time when there is widespread talk of a threat to the humanities in contemporary universities and lecturers bewail the lack of knowledge of the classical and biblical traditions among students, Cassiodorus's attempts to ward off the effects of the collapse of the institutions of public education in his day take on a new significance.  Sheffield has a number of Classically-inspired buildings, and this is one of my favourites. It is the Unitarian Upper Chapel on Norfolk Street, near the Crucible Theatre (another design inspired by the buildings of the ancient world). The chapel dates from 1847-8, and stands on the site of a much older house. Its present appearance is the work of John Frith, who based it on the Travellers’ Club in London. These are some of its features: · The roof has the unmistakable low triangular shape of the pediment of the Parthenon in Athens. It does not, however, boast the sculptures for which that temple is famous: there is only blank brickwork. You can see the little “guttae” like small cubes lining the edges of the pediment. · The upper-storey windows have a round arch shape, which isn’t found in Greek architecture as they hadn’t yet discovered how to build them! They are flanked, though, by Corinthian pilasters. A pilaster is a column shape – usually half the diameter of the whole column – attached to a wall rather than free-standing. · The front door is sheltered by an imposing porch. This has four Ionic columns with a frieze above which bears only the name of the chapel. It’s not uncommon to find two or more orders of architecture in the same building: the Parthenon itself has Doric columns as its peristyle (outer edge) and Ionic columns inside. A walk round Sheffield city centre will reveal many more Classical buildings – especially if you look up above the shop fronts! Rosemary Hulse

Click here to find out more. Report to follow on this website afterwards.

Admire Godfrey Sykes’s adaptation of the Parthenon frieze to a Sheffield context, substituting artisans, labourers, miners and steelworkers for Pheidias’ procession of Athenian horsemen. Headed by Minerva/Athena and other gods, in Sykes’s vision the workers of Sheffield proudly wield their tools and push their trucks around the whole thirteen painted panels, extending to 60 feet, of the frieze. The background of the frieze is a bright (aqua marine) blue and the figures stand out in a deep gold. Sykes was a Yorkshireman, who left his apprenticeship to an engraver and enrolled at the newly opened Sheffield School of Art in 1843. He was much influenced by the neoclassical sculptor Alfred Stevens, who designed Greek revival buildings in the area. Sykes’s other works include several paintings of people hard at work, in smitheries, forges and steelworks. Perhaps it was his reputation for sympathetic portrayal of industrial work that led, in 1854, to his being commissioned to design a frieze by the Sheffield Mechanics Institute. The Institute had opened in 1832, and had several hundred members, including one hundred women; its lecture hall could accommodate a thousand . . . for more click here  Keeping Their Marbles: How the Treasures of the Past Ended Up in Museums - And Why They Should Stay there Tiffany Jenkins

See also Tiffany Jenkins' recent blog post here

|

Sheffield branch of the Classical Association, founded in 1920

Archives

November 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed